John Moravec

John MoravecApproaches for enabling invisible learning

Note: This is the final article of a three-part series on a new theory for invisible learning.

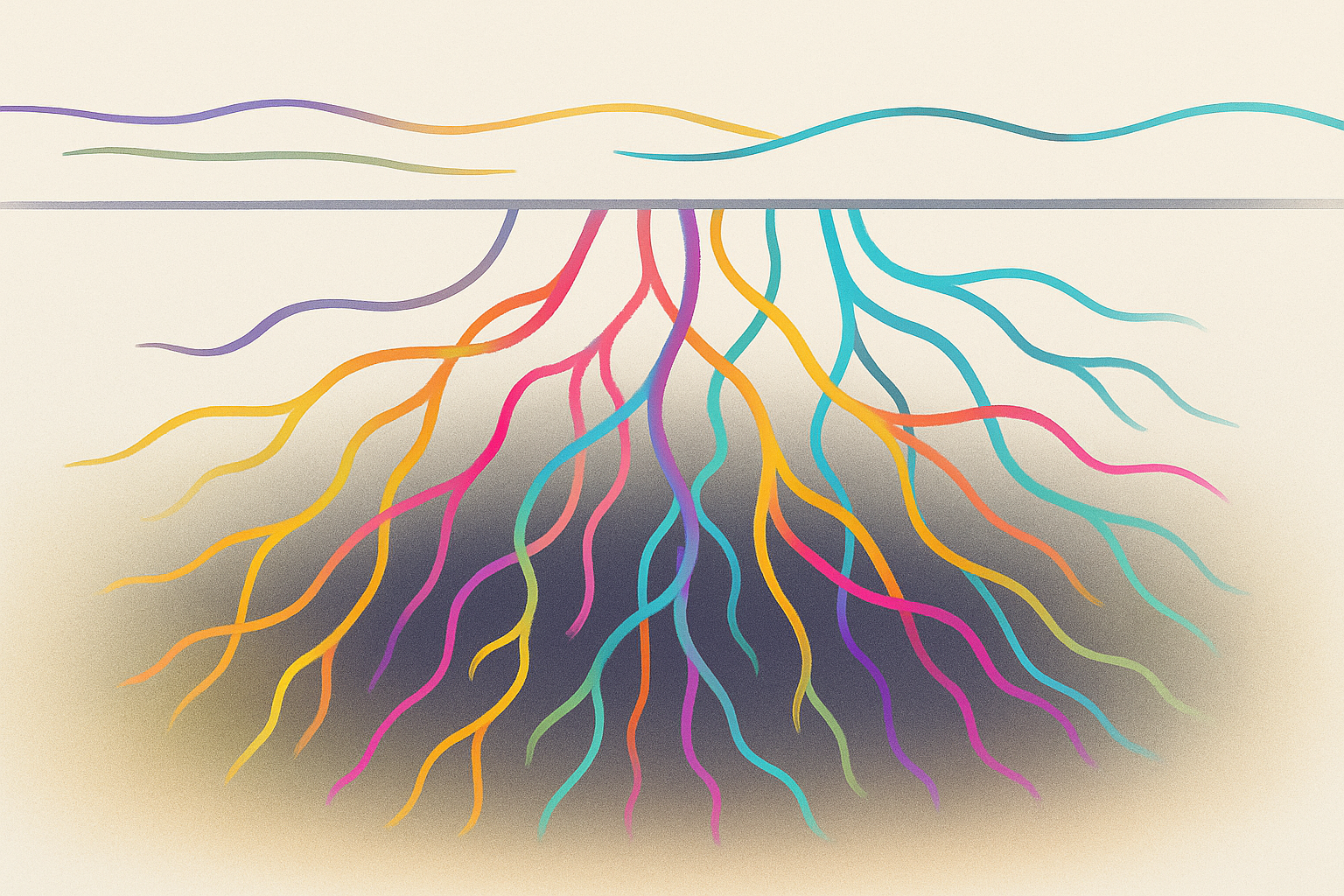

The Theory for Invisible Learning is that we learn more, and do so invisibly, when we separate structures of control that restrict freedom and self-determination from learning experiences.

Invisible learning can emerge in many ways, and often manifests through bits and pieces here and there. The examples of approaches to invisible learning provided here are not exhaustive, and are meant to be illustrative only. Each of these approaches embrace participation, play, and exploration.

Schools for invisible learning

Democratic education schools are arguably the most visible examples of enabling self-determination. From the 2005 EUDEC guidance document, students in democratic schools have the right:

to make their own choices regarding learning and all other areas of everyday life. In particular, they may individually determine what to do, when, where, how and with whom, so long as their decisions do not infringe on the liberty of others to do the same.

Sudbury-type schools embrace this principle at their core, providing each student an equal voice and vote along side staff members and other stakeholders as to what they learn and how their schools are run. Students spend their time together without age or grade separation and they decide how to spend their time at the school. Central to the school’s operation are school meetings in which students and staff members make key decisions in a process focused on participatory democracy. In these schools, students are afforded tremendous freedom together with the personal and collective responsibility to make the best decisions possible.

These schools are part of a broader category of free schools which developed over the past century, with many approaches that interpret “free” schooling differently. Some operate as full democracies, and others as anarchist collectives. Of particular importance is the Summerhill School (UK), which permits each student to develop their own lesson plans within a structured timetable. Students have the freedom to pursue their own learning interests, based on offerings, and like the Sudbury model, they operate within a framework of participatory democracy with shared responsibilities.

There is very little research on democratic and free schools compared to mainstream education, but my hunch is they best serve students of at least middle-class or better-educated families, where students have greater flexibility and support to pursue their own interests. For students in economically disadvantaged families, we can look into liberation pedagogies such as critical pedagogy, eco schools, and praxis-type schools as pathways. While their foci are often connected with particular ideologies, they share core themes of socioeconomic liberation for students and the communities in which they live.

Finally, youth organizations and community participation opportunities that exist, often connected to formal schools, provide pathways toward invisible learning. Most often, we see this through scouting, clubs, and extension programs where students are not evaluated on a rigorous program, but instead earn badges, develop creative products, and create community-relevant outcomes that are based on their own interests.

Free play and exploration

Free play is a natural human activity where invisible learning flourishes. Through play, children discover their interests and aptitudes. Play inspires curiosity to test boundaries and learn social rules and norms, together with the development of many soft skills. Unfortunately, mainstream approaches to education ignore or underplay its importance in learning. Psychologist Peter Gray defines play as:

“first and foremost, self-chosen and self-directed. Players choose freely whether or not to play, make and change the rules as they go along, and are always free to quit. Second, play is intrinsically motivated; that is, it is done for its own sake, not for external rewards such as trophies, improved résumés, or praise from parents or other adults. Third, play is guided by mental rules(which provide structure to the activity), but the rules always leave room for creativity. Fourth, play is imaginative; that is, it is seen by the players as in some sense not real, separate from the serious world. And last, play is conducted in an alert, active, but relatively unstressed frame of mind” (from an interview in Journal of Play, Spring 2013).

Play is separate from sports and other organized activities in that it is explorative and satisfies an individual’s curiosity to try new ideas or simulate different possibilities in the world. Through play, a learner’s environment becomes his or her laboratory. This satisfaction of curiosity encourages the development of auto-didacticism, the practice of learning by one’s self.

Similar to free play is free exploration within our own communities and beyond to learn from others. What happens, for example, when children explore a culture beyond their own? What do they discover? How does it change them? What skills, competencies, or insights might they develop? Many of the answers to these questions are difficult to quantify or measure, but research suggests they can be related through the development of soft skills (i.e., intercultural competence, capabilities to handle ambiguity, empathy), which are critical outputs of invisible learning. This is learning beyond codifiable curricula, and places trust in kids that they can develop their own skills.

Building cultures of trust

To break free from the structures of control, we need to build cultures of trust. We need to trust children to learn without being told what to learn. Democracies are built on trust and shared responsibility. Free play and exploration are built on trusting others to help us learn from each other.

Teachers and school leaders have many opportunities to develop pathways toward invisible learning through participation, play, and exploration. These can be realized through their own development and praxis as well as through their work with students. But, the bottom line is enabling invisible learning is centered on trust, and trusting that children always learn — no matter what. As we wrote in Manifesto 15:

“The thrill of jumping off a cliff by deciding to do so yourself is a high you will never have if someone else pushes you off of it. In other words, the top-down, teacher-student model of learning does not maximize learning as it devours curiosity and eliminates intrinsic motivation. We need to embrace flat, horizontalized, and distributed approaches to learning, including peer learning and peer teaching, and empower students to realize the authentic practice of these modes. Educators must create space to allow students to determine if, and when, to jump off the cliff. Failing is a natural part of learning where we can always try again. In a flat learning environment, the teacher’s role is to help make sure the learner makes a well-balanced decision. Failing is okay, but the creation of failures is not.”

Posts

in this series