John Moravec

John MoravecWhat the GEFRI data tells us that we didn’t expect

How ready is the world for the future of education?

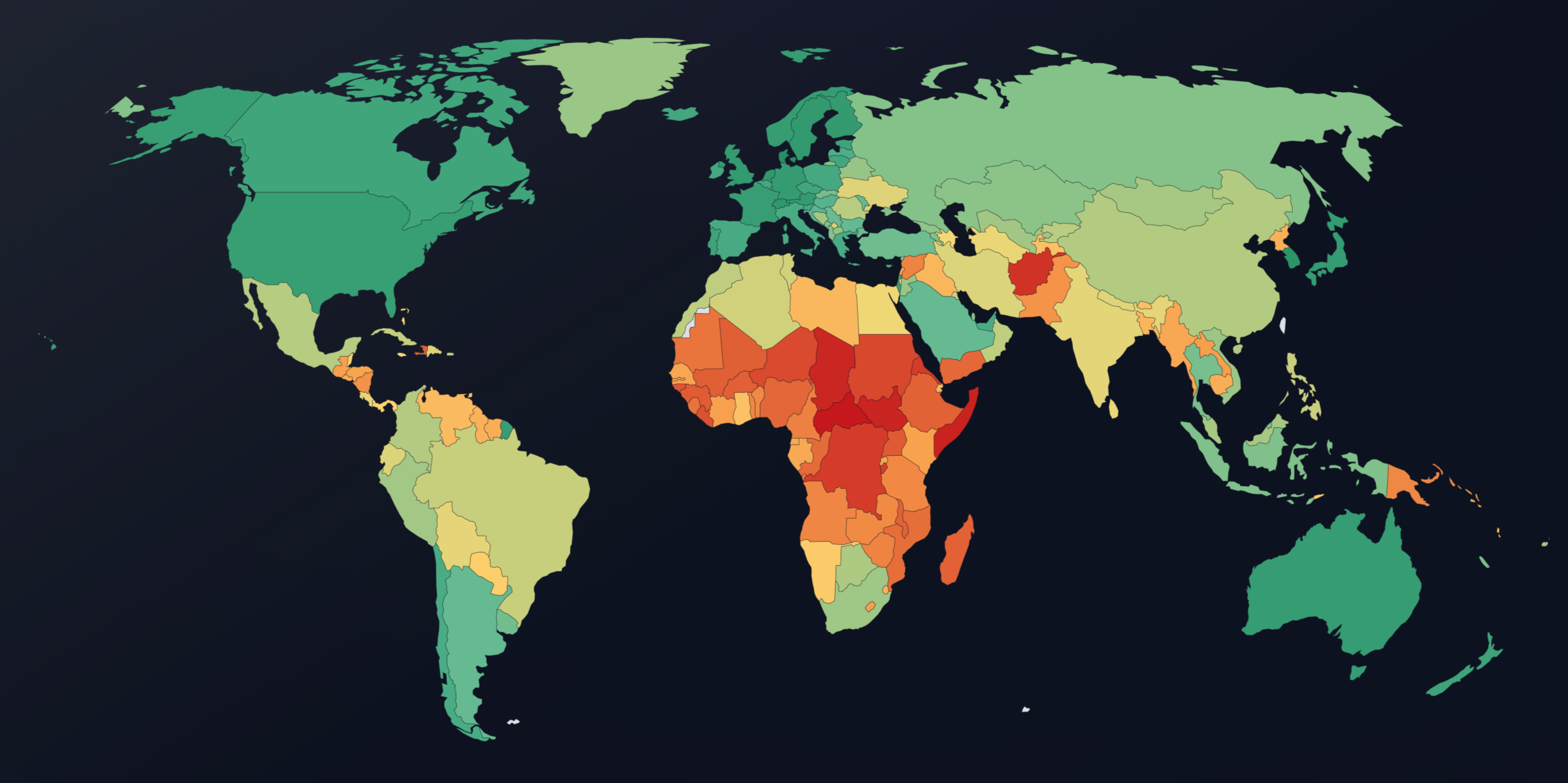

The Global Education Futures Readiness Index (GEFRI) provides the first comprehensive, data-driven answer. Covering 217 countries, including large economies, small island states, and nations in crisis, GEFRI benchmarks how prepared each is to meet the demands of rapidly changing educational, social, and technological landscapes.

GEFRI enables users to compare countries using the latest available data. Rather than prescribing rankings or solutions, GEFRI encourages discovery, comparison, and reflection on what readiness means for different contexts. It is designed to help policymakers, educators, researchers, and advocates explore patterns, identify strengths and gaps, and spark new conversations about the future of education worldwide.

Unlike traditional education rankings that focus mainly on access or test scores, GEFRI takes a multidimensional approach. The index combines five key pillars: Infrastructure, Human Capital, School Access and Gender Parity, Innovation, and Governance. Each pillar is built from internationally comparable indicators, ranging from internet access and teacher training to research activity, education spending, regulatory quality, and gender equity. The result is a composite score that reflects how well countries are equipping learners and systems for the future.

Data for GEFRI comes primarily from the World Bank and UNESCO, using the most recent and reliable sources available(see GEFRI’s methodology documentation for more detail). Where data gaps exist, the index applies a transparent imputation method, always indicating confidence in the results. Microstates and special cases are handled carefully to ensure meaningful global comparisons, while each country’s unique context is respected through both regional and income group benchmarking.

By painting a global picture of readiness, GEFRI uncovers disparities and surprising stories of resilience, innovation, and leadership. As you explore the data and insights that follow, GEFRI invites you to look beyond conventional wisdom and discover how nations across the spectrum are preparing for new futures of learning.

Myth 1: Wealth reliably equates to readiness

It’s easy to assume that a nation’s economic strength directly translates into future-ready education. GEFRI says: not so fast.

On the surface, it seems logical: wealthier nations can spend more on schools, teachers, and technology. Many global benchmarks reinforce this narrative, as high-income countries often lead on measures of enrollment, digital access, or educational attainment. But GEFRI’s approach reveals a more complex reality by going beyond simple spending figures or headline statistics.

How does GEFRI challenge this assumption?

GEFRI evaluates readiness across five core dimensions: Infrastructure, Human Capital, School Access and Gender Parity, Innovation, and Governance. Each dimension is built from normalized, internationally comparable indicators, and penalizes low confidence scores or heavy reliance on imputed data. This multidimensional lens exposes surprising patterns that single-factor measures miss.

The overperformers: Success beyond wealth

A number of lower-middle income countries consistently outperform global averages on overall readiness. For example:

- Jordan, Viet Nam, Kyrgyz Republic, Philippines, and Uzbekistan each post composite scores above the global mean, surpassing many high-income nations.

- Their strengths often stem from targeted investments in human capital, robust access policies, or dynamic innovation ecosystems, even in the absence of vast resources.

- Viet Nam, for example, is frequently cited for its high learning outcomes despite modest spending per pupil. Uzbekistan and Kyrgyz Republic have expanded access and equity, while Jordan and the Philippines demonstrate effective use of international partnerships and homegrown reforms.

These stories challenge the notion that only wealthy nations can build strong, adaptable education systems. Context matters: policy focus, system design, and social commitment can compensate for limited resources.

The underperformers: Wealth is no guarantee

Conversely, GEFRI uncovers several high-income countries whose scores fall below the global mean, including the Bahamas, Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago, and Panama. Despite robust economies and comparatively high per-capita spending, these countries score lower in one or more dimensions such as governance, equity, or innovation.

- For example, resource-rich economies may struggle with disparities in access, outdated curricula, or inconsistent policy environments.

- GEFRI’s use of a composite score makes these weaknesses visible, rather than masked by strong results in just one area.

What does this mean for policymakers and practitioners?

- Money matters, but it is not everything. Effective policy, inclusive governance, and a focus on results can propel countries forward (sometimes faster than economic might alone).

- No country can afford complacency. High-income status does not immunize a system from stagnation or gaps in readiness.

- Contextual strategies matter. Learning from lower-income overperformers can inspire innovation and reform even in the world’s most established systems.

Myth 2: Innovation only emerges in the usual places

When we think about educational innovation, the mind often jumps to the big players: Silicon Valley, global tech hubs, wealthy economies leading the charge. But GEFRI uncovers a much more nuanced reality. Some of the world’s highest innovation scores emerge from countries that are otherwise far from the top of global rankings.

Why does this happen?

GEFRI’s approach is both rigorous and revealing. The index’s Innovation dimension draws on a broad, globally standardized set of indicators, including:

- R&D expenditure as a percent of GDP

- Number of researchers in R&D per million people

- Scientific and technical journal articles per million population

- High-tech exports

These metrics are normalized, log-transformed where appropriate to correct for skewed distributions, and strictly filtered (for example, journal articles are only included for countries with populations over 1 million to avoid microstate distortion). When data is missing, GEFRI transparently imputes values using a documented, multi-step process based on region, income group, and global trends, always flagging where imputation affects confidence. In short, innovation is measured in ways that reflect the ability to produce new knowledge, as opposed to consumption.

What does the data really show?

The result is a set of “innovation outliers” that defy simple expectations. Countries such as Brazil, Egypt, Iran, Morocco, and Tunisia, and, perhaps most startlingly, North Korea, all rank in the top quartile for innovation, despite having overall GEFRI scores that fall below the global median. North Korea, in particular, demonstrates how a system can be structured to support state-driven R&D, scientific publication, or high-tech manufacturing, even amid broader systemic challenges. While these scores do not tell the full story about the openness, impact, or other qualitative dimensions of innovation (e.g., are innovations supporting a military industrial complex vs other sectors), they reveal that the capacity for technical and scientific progress can flourish in unexpected places.

GEFRI’s methodology ensures that such findings are not the product of a single outlier metric or data quirk. Each dimension is based on the arithmetic mean of several normalized indicators, and dimensions with heavy imputation receive a confidence penalty, meaning only genuinely robust performance stands out.

What does this mean for how we think about innovation?

First, it disrupts the narrative that innovation is the exclusive domain of wealthy, stable countries. Innovation ecosystems can (and do) emerge in countries facing complex social, political, or economic barriers. Sometimes, necessity drives creative solutions; sometimes, state priorities or international partnerships fuel scientific investment and output.

Second, it urges policymakers and funders to look beyond reputation or GDP when searching for innovation partners. The next breakthrough in educational technology, pedagogy, or system design could come from places rarely cited in global headlines.

And third, it demonstrates the importance of using multi-dimensional, transparent, and data-driven tools like GEFRI to surface these patterns. Without a composite approach that values research activity, tech exports, and R&D alongside access and governance, these stories would remain invisible.

In an era where innovation is essential for adapting education to new realities, GEFRI’s innovation dimension spotlights where the seeds of the future are already being planted.

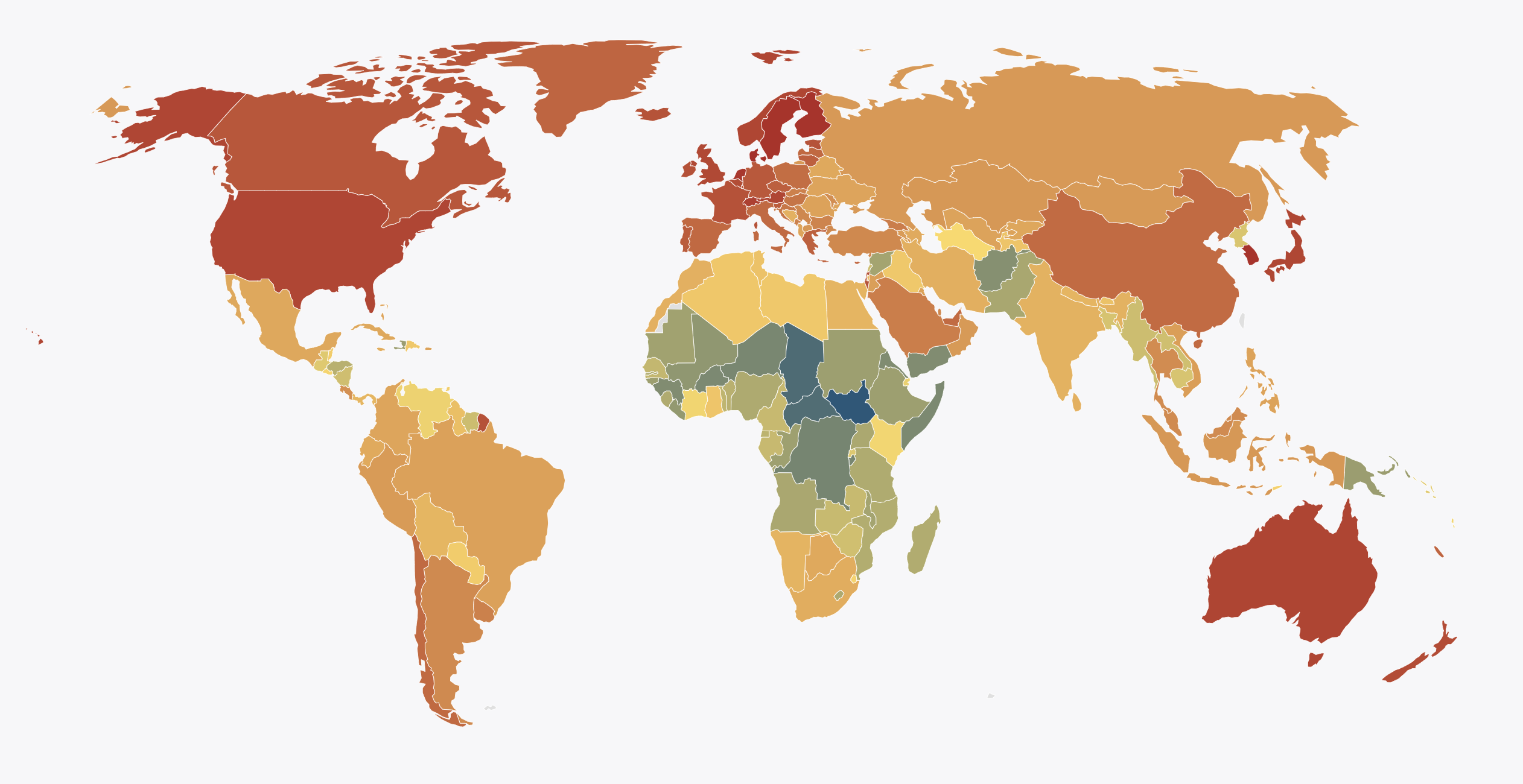

Myth 3: The usual leaders always dominate their regions

Who leads educational readiness in each region? GEFRI surfaces regional champions that are not always in the international spotlight. According to the latest GEFRI results:

- Chile tops Latin America and the Caribbean (composite score: 70.7), outpacing both regional giants such as Brazil and wealthier, smaller economies often presumed to lead.

- Israel leads the Middle East and North Africa (74.9), standing out for its robust performance across governance, innovation, and human capital.

- Mauritius is the surprising leader in Sub-Saharan Africa (60.1), reflecting years of investment in education, technology, and inclusive policy—surpassing more populous and often higher-profile nations like South Africa or Nigeria.

- Sri Lanka claims the highest spot in South Asia (52.5), outscoring regional giants like India and Pakistan despite having fewer resources.

- Korea, Rep. (South Korea) holds the top spot for East Asia & Pacific (80.5), which may not surprise some, but stands as a testament to the consistency of its long-term educational investments.

What makes these findings surprising?

First, these champions often are not the biggest economies or the best-known education “brands.” Instead, they are countries that have managed to outperform their circumstances, sometimes through targeted reforms, strong governance, or unique educational models. For example, Chile’s leadership in Latin America stems from economic growth and also from deliberate policy choices around access, quality, and accountability.

Second, the presence of “non-traditional” leaders highlights that progress is possible regardless of size, GDP, or international reputation. Mauritius, with a small population and a location far from global education power centers, has emerged as a continental leader through steady, inclusive investment and policy innovation.

Third, these regional leaders often embody a diversity of approaches. Israel’s strengths in research and technology drive its composite score, while Mauritius blends social inclusion with steady development and Chile’s system features strong school access and governance.

Why does this matter?

These findings challenge governments, international agencies, and funders to broaden their view of “what works” in education futures. Rather than assuming solutions must come from the same handful of “global leaders,” GEFRI encourages the world to learn from a wider range of models and to pay attention to regional contexts and realities.

For regional policymakers, the data serve as a call to consider:

- Benchmarking against the global average and against the most effective neighbors.

- Exploring the strategies that have enabled regional peers to excel, even if those stories do not usually make international headlines.

For international organizations, these results highlight the value of south-south learning, regional collaboration, and context-sensitive policy transfer. The world’s next educational leap might emerge from places not previously considered “leaders,” but now, thanks to GEFRI, visible as role models.

Myth 4: Fragility means futility

The prevailing narrative in global education holds that fragile and conflict-affected states (FCS) are destined to lag far behind in educational readiness. It’s easy to assume that instability, limited resources, and institutional breakdowns create insurmountable barriers to progress. While GEFRI’s global results do show that fragility remains a serious challenge, the data tells a more complex story.

GEFRI’s approach to fragility

GEFRI explicitly identifies and analyzes fragile and conflict-affected states using the latest lists and definitions from the World Bank and international partners. In these contexts, GEFRI applies additional transparency and caution:

- Scores for FCS are capped at 40 in the School Access and Gender Parity dimension, to reflect deep structural barriers not fully captured by quantitative indicators.

- All imputed data and low-confidence scores are clearly flagged, ensuring that results for FCS are interpreted with appropriate caution.

- Despite these limitations, GEFRI includes FCS in all global and regional calculations, making it possible to track their position (and outliers) within the international landscape.

The reality: A wide, but not absolute, gap

The numbers are sobering:

- The average GEFRI score for fragile and conflict-affected states is just 31.2, compared to 56.2 for non-FCS countries—a gap of 25 points, more than a full standard deviation.

- The largest gap appears in School Access and Gender Parity (nearly 38 points), but substantial differences are also seen in Governance, Infrastructure, and Human Capital.

At first glance, these results might seem to reinforce the idea that fragility equals futility. But GEFRI also surfaces a handful of FCS that defy the odds, posting scores far above the FCS average and, in some cases, approaching or even surpassing global means in specific dimensions.

Outliers: Stories of resilience and progress

GEFRI’s results reveal that progress is possible even in the most challenging contexts. Despite a history marked by conflict and ongoing institutional hurdles, Kosovo achieves a composite score of 61.2, well above the average for fragile states and surpassing many more stable nations. Its strong performance is driven by targeted education reforms, international partnerships, and a striking innovation score that rivals wealthier peers.

Tuvalu tells a different story. This tiny Pacific island nation, vulnerable to both climate and economic shocks, outperforms its fragile-state peers also also many non-fragile countries of similar size or wealth, with a GEFRI score of 57.3. Tuvalu’s achievements reflect steady investment in teachers, inclusive curricula, and creative adaptation to local and global challenges, demonstrating that size and resources need not limit a country’s educational ambitions.

These outliers embody what is possible through deliberate investment, adaptive policymaking, and strong community or national will, even under stress. Kosovo and Tuvalu remind us that educational transformation is not reserved for the wealthy or the stable. With vision and determination, resilience and progress can take root anywhere.

Why these insights matter

What does it mean when the data challenges everything we thought we knew about education’s future? GEFRI’s findings demand that we look deeper, act smarter, and build solutions that are not connected to old assumptions.

First, data-driven insight breaks stereotypes. It’s easy to assume that wealth, peace, or international reputation guarantee readiness for the challenges ahead. But GEFRI demonstrates that progress and innovation often emerges in unexpected places. Countries facing adversity can leap ahead. Traditional leaders sometimes lag. Regional champions may not be who you expect.

Second, nuance matters for futures readiness. Simple league tables can hide the actual story. By disaggregating by region, dimension, and context (and showing the impact of missing or imputed data) GEFRI data reminds us that no single path leads to future-ready education. Policymakers, donors, and practitioners need to look at how countries succeed, not just if they do.

Third, this is a call for global learning and partnership. If we want every learner to be ready for tomorrow, we need to learn from the world’s full diversity of experience. This means championing regional innovations, supporting development even in fragile contexts, and amplifying outliers who defy the odds.

GEFRI’s open methodology, visible confidence ratings, and detailed data handling make it a tool for conversation and collaboration beyond simple competition. It invites countries to tell their own stories, spot their strengths and gaps, and set a course for real progress.

Ready to see where your country stands and what you can learn from the world?

Explore the GEFRI dashboard and join the conversation about the future of learning.