John Moravec

John MoravecHow Big Tech is silently colonizing education

Educators face a growing sense of concern about artificial intelligence. New tools enter classrooms faster than policies can adapt. National authorities release guidance documents that outline principles for safe or ethical use. Universities add statements to their syllabi about transparency and good conduct. Companies offer free training modules that show teachers how to integrate their platforms into lesson plans. These efforts have value, yet they sit on the surface of a deeper problem. Most decisions that shape how AI works occur far from the people who will live with the consequences.

When we talk about “using” AI in education, we often miss the larger reality shaping its arrival. The tools entering classrooms are not simple instruments. They come from a small group of firms that set the terms of access, define the rules of interaction, and shape how knowledge circulates. The rapid spread of these systems is guided, but not by educators. It reflects the priorities of companies that benefit when institutions adopt their platforms as default infrastructure. Educators may receive training and safety modules, yet they do not participate in the decisions that govern model behavior. This distance creates a form of dependency that weakens professional judgment and shifts control away from the public sphere.

Much of the current dialog treats AI as if it belongs in the same category as calculators or mobile phones. This analogy serves Big Tech well. It frames adoption as inevitable and harmless, and it encourages educators to focus on classroom management rather than on the structural forces shaping the tools themselves. It also masks the fact that earlier technologies did not carry embedded economic or political interests. AI does. When we rely on analogies that flatten these differences, we make it easier for companies to define the terms under which education will engage with them.

I explore that gap here. My argument is that education cannot meet its responsibilities if it approaches AI only as a question of classroom practice and control. The deeper issues lie in governance, institutional capacity, and the long history of how schools respond to new technologies. To make this case, I draw on examples from GEFRI, Manifesto 25, and Goblinly.

An abundance of frameworks with an absence of agency

AI enters education through a constant stream of frameworks and guidelines. They outline principles for transparency and safety, and they promise to help teachers navigate risk. Many come from credible institutions, yet they share an important feature: they focus on the behavior of educators and students, not on the systems that shape their choices. As a result, these frameworks normalize Big Tech’s presence. They train educators to adapt to platforms rather than question the power behind them.

Frameworks alone cannot compensate for the structural reality that teachers and institutions do not control the systems they are told to “use responsibly.” Ethical guidelines emphasize individual behavior rather than the priorities of the organizations that build and deploy AI. They describe responsible practice as something achieved through vigilance, documentation, and consistent checking of outputs, while the systems themselves remain outside institutional control.

This emphasis on user behavior signals a deeper problem. When responsibility sits with the user but power sits with the developer, the framework becomes a moral contract without a mechanism for shared governance. Educators follow rules they did not create. They navigate constraints they did not choose. They bear the professional risk associated with systems that operate beyond their view.

In earlier technological cycles, schools regulated the tools they allowed into classrooms and set the terms of their use. With AI, the flow reverses. The tools regulate the schools. Algorithms determine what students see. Content filters shape what they can ask. Recommendation engines encourage particular forms of inquiry. These mechanisms operate quietly, yet they redefine the boundaries of instruction. The shift from institutional authority to platform authority introduces a structural imbalance that many systems are not equipped to manage.

This imbalance appears in national readiness assessments. GEFRI, for example, distinguishes infrastructure from innovation, human capital, governance, and equity. Many countries rank high on access to devices and connectivity but score lower on governance, which signals limited capacity to steer and regulate technology rather than merely adopt it. The result is a pattern in which education systems look prepared because they possess the technical means to use new tools, yet lack the institutional depth needed to guide them toward public goals.

Frameworks help educators use AI within those systems. They do not grant influence over how AI evolves. This distinction matters because education is not a neutral environment. It is a public institution charged with supporting human flourishing, civic life, and broad participation in knowledge. If educators only receive instructions about how to act within someone else’s design, the profession loses its claim to shape how learning technologies serve society.

AI as the latest chapter in a long history of control

AI feels new, but the surrounding issues are familiar. Schools have long struggled with new technologies. Calculators were seen as shortcuts that would impair reasoning. Mobile phones were framed as distractions that would destroy concentration. Even printed books have, at various times, been governed by lists of approved titles or removed from shelves. In each case, institutions responded with a mix of fear, restriction, and eventual accommodation.

The pattern reveals something important. Schools tend to approach technology as a matter of control rather than understanding. The first instinct is to regulate rather than ask what kind of cognitive or social shift the technology represents. This dynamic repeats now with AI. Many policies emphasize detection of misconduct, prohibition of certain uses, or close monitoring of student behavior. These responses address immediate concerns, yet they rarely engage with the underlying shifts in epistemology, authorship, and authority that AI brings.

This tendency toward control rather than inquiry keeps education tethered to past structures. Manifesto 25 argues that mainstream education systems respond to global uncertainty with tighter discipline, standardized expectations, and rigid compliance cultures—seeking stability through fear, compliance, and control.

AI heightens this tension. Schools fear cheating, misinformation, and the erosion of trust. At the same time, companies market AI as a solution to labor shortages, administrative burden, and student disengagement. Educators feel pressure from both sides: contain AI to preserve integrity, adopt AI to improve efficiency. Neither impulse addresses the deeper question of what it means to teach and learn in an environment shaped by powerful, opaque systems.

Education requires structure. The challenge is to notice when control becomes a substitute for understanding. AI compels a more reflective approach. It asks educators to examine why they repeat restrictive patterns, what fears those patterns express, and what possibilities they obscure.

The illusion of “using” technology

We often assume that teachers use technology. We say that educators “use” learning management systems, “use” digital assessments, and now “use” AI tools to plan lessons or evaluate student work. This language implies human agency. It frames the teacher as the operator and the tool as the instrument.

But the reality is more complex. Platforms guide behavior in ways that feel natural yet are deeply structured. Default settings influence what teachers notice. Recommendation engines shape what students encounter. Safety layers define the boundaries of acceptable knowledge. Analytics dashboards determine which forms of evidence appear meaningful. Teachers operate these systems, but the system’s architecture steers their choices.

This is where colonization becomes visible. Big Tech’s influence enters through those same defaults, settings, and design decisions that limit educator agency while giving the impression of control. The interface encourages particular actions. The safety layer narrows what counts as legitimate inquiry. The analytics dashboard frames progress in specific terms. Long before anyone makes a decision, the platform has already shaped the conditions of practice and performance.

Douglas Rushkoff captures this dynamic in his call to “program or be programmed.” Programming in his sense refers not only to writing code but to understanding how systems behave and how they shape human action. Without that understanding, users adapt to systems rather than shape them.

Educational AI now trains its users in subtle ways. “Ethical use” modules instruct teachers on how to act. They outline responsibilities and risks but rarely explain how the platform manages data, sets boundaries, or interprets ethical principles. The burden shifts downward. Teachers become enforcers of student conduct, even though they cannot see inside the systems that define the rules. Students, in turn, learn to trust outputs because the interface presents them as stable and fluent.

Some tools challenge this orientation. Goblinly, for example, treats AI as an object of examination rather than a source of truth. Students receive outputs from playful personas that blend insight with error. Their task is not to accept the answer but to inspect it. They build skill by noticing patterns of reasoning, moments of overconfidence, and the subtle misalignments that often hide in fluent prose. The platform trains skepticism and deeper literacy over blind acceptance of machine outputs.

This illustrates a shift in how we should perceive AI in education. When learners treat AI as something to interrogate, they become less susceptible to its illusion of authority. They develop practices of questioning, cross-checking, and resisting the superficial coherence of machine-generated text. These practices carry beyond the classroom. They form part of a broader public literacy needed in a world where AI will become a routine generator of content and claims.

Readiness without sovereignty

Policymakers often advocate for AI “readiness.” They invest in broadband, devices, and large digital platforms. They treat access as the primary barrier to participation in a global technological economy. In this framing, AI appears as another tool nations must deploy to remain competitive.

Yet readiness is not the same as control. A system can have robust infrastructure and still depend on external technologies that it cannot influence. It can adopt advanced platforms while absorbing assumptions, values, and governance structures that originate elsewhere. The surface looks modern, but the capacity to guide technology in the public interest remains limited.

These gaps do not amount to a formal loss of sovereignty, but they create conditions in which outside actors gain quiet influence. When public systems rely on technologies they cannot meaningfully evaluate or modify, they become subject to the priorities and update cycles of the firms that supply them. Dependence becomes the channel through which colonization emerges.

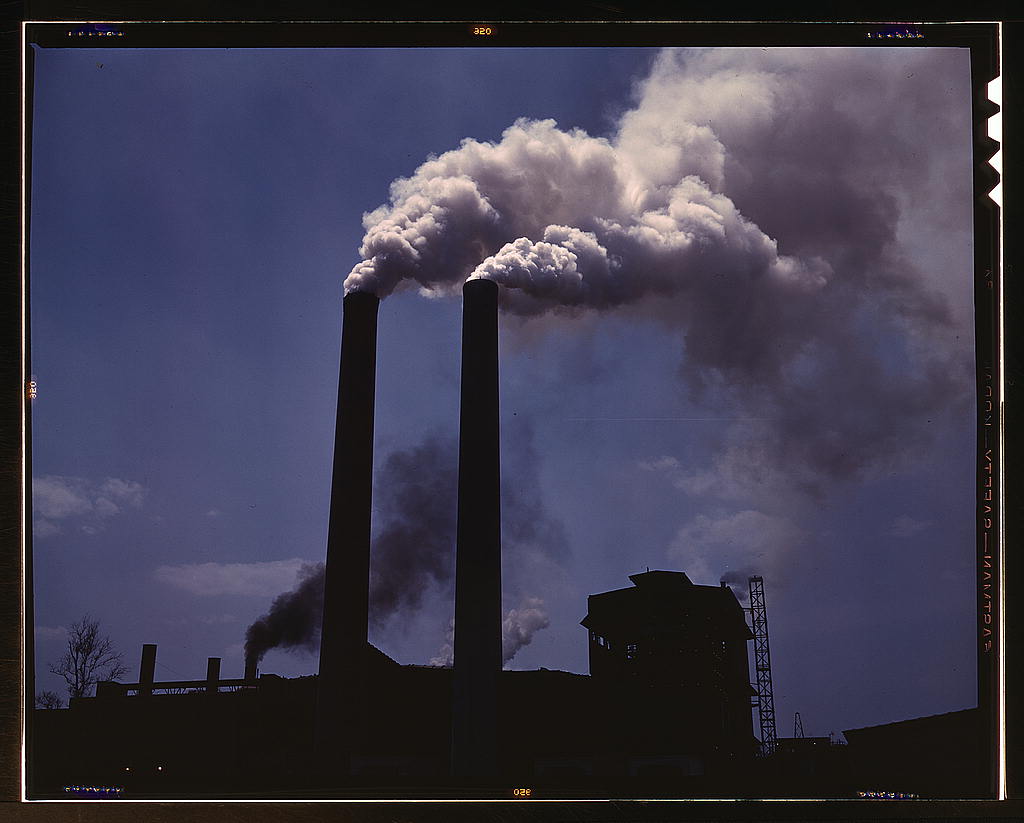

Big Tech exploits these conditions. When nations depend on external AI infrastructure, companies become unaccountable partners in the governance of public education. Their models shape how students search, write, and ask questions. Their terms of service determine what data flow out of classrooms. Their product decisions influence entire curricula. This is colonization through dependency: not imposed by force, but accepted through reliance on private systems as public infrastructure.

The challenge is not to reject external tools. Global collaboration and shared innovation matter. The issue is how to balance adoption with the capacity to steer. Education systems need the ability to question, negotiate, and demand transparency. They need institutional memory and professional expertise to assess new systems before they become entrenched. Without this grounding, AI adoption may accelerate dependence rather than strengthen public institutions.

Misplaced responsibility bears a social cost

When responsibility for ethical AI use is placed almost entirely on individuals, the burden becomes unsustainable. Educators are asked to monitor student conduct, ensure compliance, manage privacy risks, and check AI-generated text for accuracy. They do this in environments where they have limited control over the systems themselves.

This imbalance produces several effects. Teachers experience rising anxiety about misconduct and misplaced trust. Students receive mixed signals about what counts as legitimate learning. Institutions invest time writing detailed AI policies, yet these documents often shift the risk rather than address its causes. When something goes wrong, individuals feel compelled to justify their choices even when the platform design shaped those choices.

The pattern resembles a larger condition: systems offload responsibility onto individuals while maintaining structures that resist transformation. Provided an illusion of control, people feel accountable for outcomes they did not design and can never fully influence. This dynamic undermines agency. It frames education as a site of risk management and compliance rather than a space for shared inquiry and purposeful development.

This pattern mirrors a classic colonial logic. Responsibility flows downward while authority flows upward. Teachers are asked to safeguard integrity and manage risk, even though they cannot influence the systems that generate those risks. Big Tech remains insulated from accountability. Its platforms set the conditions under which misconduct becomes possible, yet educators and students bear the consequences.

A more balanced approach would align responsibility with actual influence. Educators and students should participate in decisions about which tools to adopt, how they are evaluated, and what safeguards are required. Institutions should demand clear information from vendors about data practices, model behavior, and documented limitations. Policymakers should create mechanisms for independent audits and community oversight. These measures shift responsibility upward into governance rather than downward into individual compliance.

Rebalancing the relationship between education and technology

If education continues to accept a passive role in the expansion of AI, it risks ceding its remaining autonomy to systems built for corporate priorities rather than public ones. Colonization in this context arrives through quiet consent. It emerges through defaults, narratives of inevitability, and the steady normalization of external control. Educators may develop more frameworks, but they will be forever trying to catch up with changes and will miss opportunities to address the deeper imbalance between the institutions that design AI and the institutions expected to absorb it. In such a space, control measures multiply at the expense of agency and enabling self-efficacy to learn.

The work ahead is institutional, cultural, and political, in addition to requiring technical change. It involves building environments where teachers and students are not only rule-followers but co-designers of their technological landscape. It involves claiming time, space, and authority for reflection. And it requires the courage to question systems that promise efficiency but weaken autonomy. This work begins when educators refuse to let AI define the terms of its integration and instead place education’s values at the center of the conversation.