John Moravec

John MoravecBad use of technology is a symptom, not the problem

When technology appears to fail in education, we’re quick to blame the tools: “The platform is outdated,” “The AI tutor doesn’t work,” or “Students are distracted by their devices.” Yet, these failures aren’t the root cause; they’re symptoms of a deeper dysfunction in how we fundamentally approach learning. This is an old problem we’ve long understood but have done little to address, with educational systems stubbornly clinging to outdated models despite decades of mounting evidence and critique.

As we wrote in Manifesto 25:

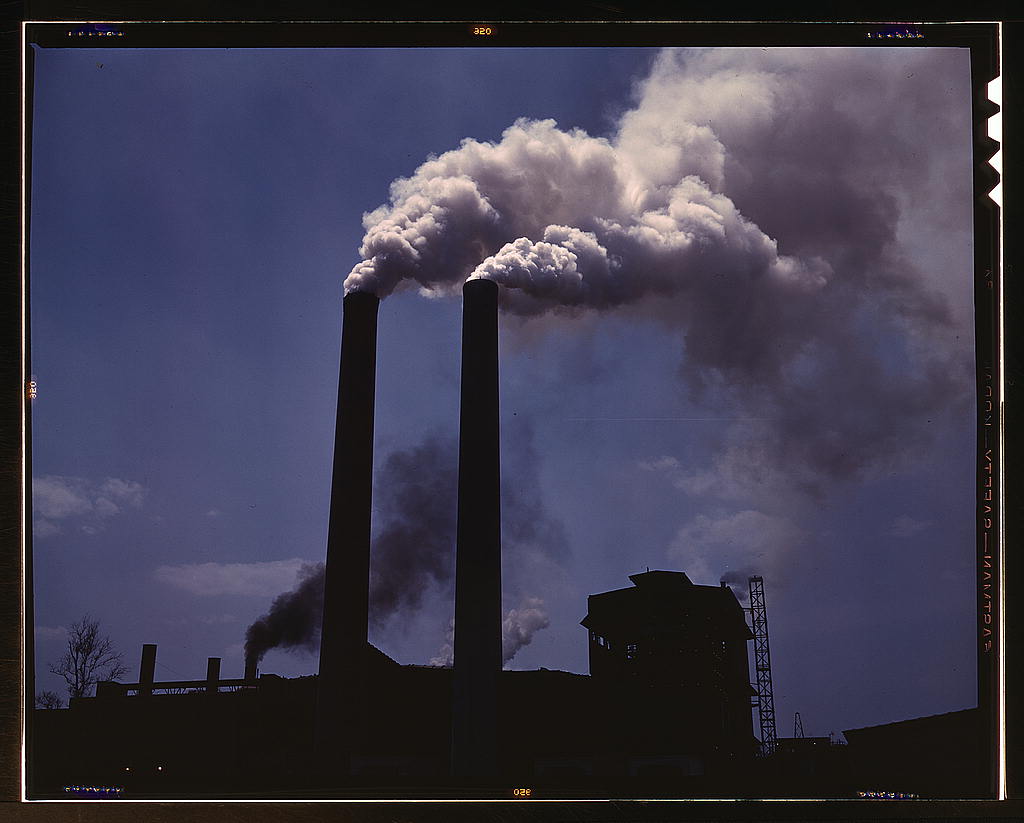

Bad use of technology is a symptom, not the problem. Technology is not a solution by itself, but when used thoughtfully, it can unlock new ways of learning and creating. We must move beyond old practices and truly harness technology as a tool for transformation, rather than obsessing over the latest tools while neglecting their potential to drive change. Swapping blackboards for smartboards or books for tablets while clinging to old teaching methods is like building a nuclear plant to power a horse cart: wasteful and ineffective. Yet, nothing has changed, and we still focus tremendous resources on these tools and squander our opportunities to exploit their potential to transform what we learn and how we do it. By recreating practices of the past with technologies, schools focus more on managing hardware and software rather than developing students’ mindware and the purposive use of these tools.

A simple analogy clarifies this point: a hammer, a basic form of technology, can be used to construct or to demolish. Its impact depends entirely on how it is wielded. This same principle must be applied to technology in education.

The fundamental issue is that current education systems are often designed for efficiency and control, remnants of an industrial-era model ill-suited for the realities of a fast-changing, uncertain world. In this top-down paradigm, knowledge delivery is prioritized, and success is predominantly measured by compliance rather than creativity or genuine understanding. When innovative technologies are introduced into these rigid structures, they are frequently co-opted to reinforce, rather than disrupt, these outdated methods.

Consequently, digital tools become little more than glorified textbooks, offering passive consumption. Artificial intelligence, instead of expanding human potential, is often confined to automating mundane tasks like grading. Learning management systems primarily organize content delivery rather than fostering true engagement and collaborative knowledge construction. In essence, technology, rather than serving as a catalyst for educational transformation, is paradoxically used to make traditional, often ineffective, teaching practices merely more efficient. The predictable result is frustration, disengagement, and resistance, not because the technology itself is flawed, but because it is being applied to bolster a status quo within a system fundamentally unequipped to harness its true transformative power.

Teachers, too, are often left without the support, training, or autonomy to truly innovate. They are told to integrate technology but are rarely given the freedom to rethink their roles as facilitators of learning rather than content deliverers. Meanwhile, students, unable to escape this world of rapid change and radical transformation, find themselves constrained by structures that demand passive absorption rather than participation and active knowledge creation.

Therefore, if technology appears to be failing in education, the solution is not to simply inject more tools into the existing framework. A profound redesign of the learning experience from the ground up is imperative. This necessitates a shift beyond the archaic notion that education is solely about knowledge transfer. Instead, it requires a refocused commitment to creating environments where students learn how to navigate complexity, solve novel problems, and actively shape their own futures. Technology, in this paradigm, should unequivocally amplify human potential, not replace it.

This transformation demands a rethinking of the very architecture of learning. Schools and institutions must evolve from systems of rigid control to dynamic platforms for exploration and co-creation. Learners should be granted genuine agency in how, when, and where they learn. Teachers, in turn, must be empowered to act as visionary designers of knowledge experiences, moving beyond their traditional role as mere content purveyors. Rather than attempting to automate education, we should be leveraging technology to support more adaptive, personalized, and profoundly meaningful learning journeys.

Ultimately, the perceived “bad use of technology” is merely a symptom. The root problem lies in our persistent application of 21st-century tools to a 19th-century education model. Until we courageously address this fundamental disconnect, no amount of “new technology” will fix what is broken; it will only make an outdated system more efficient at producing outdated outcomes.

Read and sign Manifesto 25 at https://manifesto25.org

Recommended readings

Perkins, D. N. (1986). Knowledge as design. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Selwin, N. (2021). Education and technology: Key issues and debates. Bloombury.