The biggest problem in mainstream education is that it does precisely what it is designed to do

In many the conversations about design thinking in schools, we tend to assume that mainstream education is poorly designed. What if it wasn’t? Form follows function, right?

From Knowmad Society (p. 42):

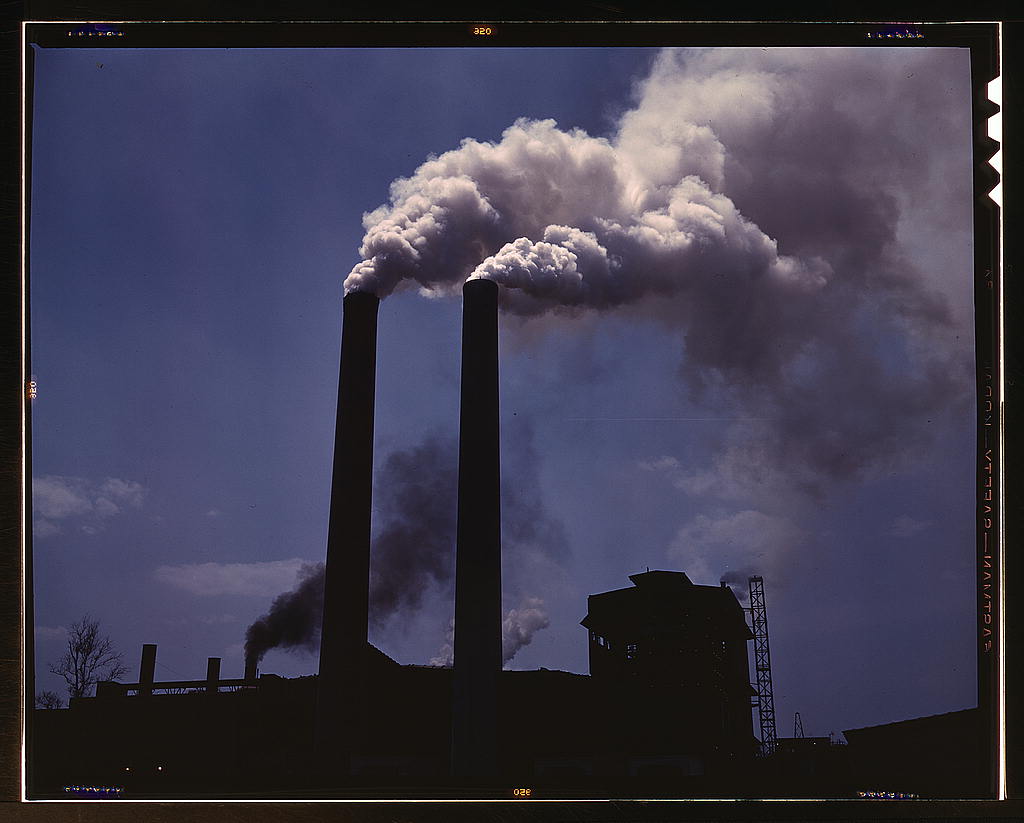

The industrialization of Europe was accompanied by social, economic, and political transformations that impacted education directly. Regents sought to replace aristocratic rulers with citizens instilled with national pride and a willingness to work for the “good” of their country. At the same time, economic growth required more factory workers and government bureaucrats to manage the system.

To meet these needs, Frederick II of Prussia, initiated in 1763 what may be considered the most radical reform in the history of education: Compulsory schooling. All children in Prussia between the ages of five and 13 were required to attend schools, which were developed into properties of the state. Principles of industrial production were applied to classrooms, which were segregated by age. pupils were aligned at desks, facing the head, where the teacher, bestowed with the absolute authority of the state, “downloaded” information and state ideology into their heads as if they were empty vessels.

The result: The state produced students that were loyal to the nation and had the potential of becoming capable factory workers and bureaucrats. This industrial model of compulsory education gained popularity in Europe, and, eventually, it was adopted throughout Western Civilization, where it remains the prevalent model of education today.

Source: Moravec, J. W. (2013). Rethinking human capital development in Knowmad Society. In J. W. Moravec (Ed.), Knowmad Society. Minneapolis: Education Futures.

Photo credit: Alfred T. Palmer, Library of Congress collection