Education Futures

Education FuturesDesigning the future of research libraries and special libraries in Knowmad Society

Paper prepared for Congreso Amigos 2015, Ciudad de México

John W. Moravec, Ph.D.

Founder, Education Futures LLC

[email protected]

October 1, 2015

Abstract

In an era consumed with accelerating technological and social change, coupled with rapidly evolving organizational needs and missions, research libraries and special libraries need to reframe why, how, and for whom they exist and explore new pathways to realize these functions. This paper explores a strategic framework to navigate a society in constant flux, disentangling information, knowledge, and innovation. We plot a pathway for maximizing creativity and innovation capital for libraries in knowledge-based institutions, together with the communities they serve.

Paper type: Conceptual

Keywords: innovation; knowledge-based organizations; research libraries; special libraries; strategic leadership; Knowmad Society

Introduction

Research libraries and special libraries are finding themselves at a crossroads. Having served as keepers of static bodies of information, they are increasingly tasked with supporting the generation of new knowledge in a world that is becoming seemingly more chaotic and ambiguous. In an interview with Paul Zenke (2012), Steven Bell, Associate University Librarian for Research and Instruction at Temple University suggests, “what can we do as academic librarians to better prepare ourselves for what is certainly an uncertain future? We just have to think more entrepreneurially and look for these opportunities.”

How does an academic library or special library reframe itself in an emerging reality that demands more innovation in the roles and services they might provide? In this paper, we propose a strategic leadership framework for understanding and designing the future of research and special libraries in Knowmad Society.

The challenge of Knowmad Society

In the introduction to Knowmad Society, Moravec (2013a) writes:

The emergence of Knowmad Society impacts everybody. It is a product of the changes in a world driven by exponential accelerating technological and social change, globalization, and a push for more creative and context-driven innovations. It is both exciting and frightening. It presents us with new opportunities, challenges, and responsibilities. And, we recognize that in a world of accelerating change, the future is uncertain. This prompts a key question: In a world consumed with uncertainty, how can we ensure the success of ourselves as individuals, our communities, and the planet? (p. 18)

This question extends especially to research libraries and special libraries. How can these institutions survive and thrive in an era that is not based on the availability of information, but instead on the contextualized use of knowledge to solve new problems?

Knowmads are nomadic knowledge workers, who are creative, imaginative, and innovative, and can work with almost anyone, anytime, and anywhere (Moravec, 2008). As citizens of Knowmad Society, knowmads are individuals who, “are valued for the personal knowledge that they possess, and this knowledge gives them a competitive advantage. Knowmads are responsible for designing their own futures […And,] a knowmad is only employed on a job as long as he or she can add value to an organization. If not, it’s time to move on to the next gig.” (Moravec, 2013a, p. 19).

The growth of knowmadic, contingent, or otherwise contract employees in the workforce changes the face of knowledge-based organizations. By the year 2020, it is projected that 45% of the workforce will be knowmadic (Moravec, 2013a, p. 19). For these contingent workers, a greater focus is now placed on how they add value – particularly at the individual level – within institutions.

Knowmad Society is also rooted in the reality of an exponentially-growing abundance of information (see esp. The Law of Accelerating Returns popularized by Kurzweil, 2005), and most of this does not reside in libraries. Whereas libraries used to have an important and definite role in providing information as a scarce resource, the abundance of information readily available elsewhere combined with a rapidly changing society that demands different information than may be found in libraries. This obviates many of the roles libraries traditionally held. How can a reference library compete with Google or Wikipedia? How can a film library compete with Netflix or YouTube? How can a corporation’s special library keep up with the ever-changing demands of the business as the organization “pivots” to meet new market realities?

For knowledge-based organizations that possess research or special libraries, the role of the library needs to be re-missioned from being a passive resource into a strategic organizer. The library needs to support and enable individuals and teams within organizations to add the greatest value they can, including supporting intrapreneurs (entrepreneurs within the organization) that take risk to create new value.

Challenges knowledge-based organizations face in Knowmad Society

Challenges to conventional wisdom faced by knowmadic organizations are numerous. They may be pressured by the de-hierarchization of leadership (i.e., shared leadership and responsibility), often expressed as organizational flattening. And, they are pressured by the accelerating pace of changes in technology and society (Moravec, 2013b). This means those at the top of an institution’s hierarchy need to consider relinquishing control of what information, knowledge, or strategic goals they believe to be the most important, otherwise risk becoming institutional laggards themselves.

Moreover, our relationships with information and knowledge are transforming, and too often their meanings are commingled. Information is constructed from bits and pieces of data. Knowledge is built by making personal meaning from information (Polyani, 1966). Innovations emerge when individuals and groups take action with what they know to create new value. While we are good at managing information, we cannot manage the personal knowledge created in the heads of our workers. And, human capital in knowledge-based organizations is becoming increasingly more expensive (see esp. Baumol & Towse, 1997). We cannot get the same efficiency gains from human systems as we can from machine systems. Our old approaches, built from principles of “scientific management,” simply do not work anymore.

Invisible learning in the age of knowmads

Invisible learning is a recognition that most of what we learn is “invisible” – that is, learning is achieved through non-formal, informal, and even serendipitous types of knowledge building. While this applies especially to schools, it is also relevant within other learning organizations. Cobo & Moravec (2011) write (translated by the authors):

The result of several years of research, invisible learning is a conceptual proposal, and it seeks to integrate various approaches into a new paradigm of learning and development that is especially relevant in the 21st century. This approach takes into account the impact of technological advances and changes in formal, non-formal, and informal education, in addition to the intermediary metaspaces between them. This approach aims to explore an overview of options for creating education that is future-relevant today. Invisible learning does not propose a formal theory, but instead presents a metatheory capable of integrating different ideas and perspectives. It has therefore been described as a protoparadigm, which is in a beta phase of construction.

1. It is a socio-technological conceptual archetype for a new ecology of education from collected ideas that combine and reflect on learning that is understood as a continuum that extends throughout life and can occur at any time or place. This approach is not restricted to a particular learning space or time, and it proposes to incentivize strategies that combine formal and informal learning. This perspective seeks to stimulate reflections and ideas on how to obtain an education that is more relevant, and one that reduces the gap between what is taught in formal education and what the labor market demands.

2. Invisible learning is also viewed as a search for remixing forms of learning that include continuous portions of creativity, innovation, collaborative and distributed work, and experimental laboratories – as well as new forms for translating knowledge.

3. Invisible learning is not suggested as a standard answer for all learning contexts. Rather, what is sought is that these ideas may be adopted and adapted to meet the specific and diverse needs of each context. While in some contexts, it can serve as a complement to traditional education, it may be used in other spaces as an invitation to explore new ways of learning. Many approaches to education seek to operate from the top-down (government control, the control of educational processes, policy approaches, etc.); Invisible learning instead proposes a revolution of ideas from the bottom-up (“do it yourself,” “user-generated content,” “problem-based learning,” “lifelong learning,” etc.).

4. Invisible learning suggests new applications of information and communications technologies (ICTs) for learning within a broader framework of skills for globalization. This proposal includes a broad frame of competencies, knowledge, and skills that fit a context to increase levels of employability, promote the formation of “knowledge brokers,” or expand the dimensions of traditional learning. (pp. 23-24)

Knowledge development within the invisible learning paradigm suggests significant implications for knowledge-based organizations. If an individual is able to find equivalent information via Google or some other ubiquitous, digital platform then the role of a library as an information provider needs to be reconsidered. Likewise, libraries need to recognize themselves not as information banks, but as connectors of information for new knowledge creation.

Of paramount importance, the relationships between consumers (e.g., individuals, research teams, and workgroups) and libraries need to shift from one where the library serves as a resource toward one where opportunities for creative remixing and new knowledge development are facilitated. This suggests that libraries, utilizing new information communication technology (ICT) applications, can play a critical role in connecting individuals and groups together to build synergies that otherwise would not be supported within an institution. In this role, the library remissions itself from being an access point of information toward an architect of connection making between points of information, knowledge, and expertise.

A leadership framework for libraries to navigate a rapidly changing society

The topic of innovation is a frequent target within academic and business literature. Many authors seek to describe modes and types of innovation within organizations, for example: Clayton Christensen’s (1997) disruptive innovation, Thomas Kuhn’s (1962) breakthroughs through scientific revolutions, and Gibbon’s et al’s (1994) Modes I and II dynamics of knowledge production through research. We build upon the spirit of these works to propose a framework that focuses on strategic leadership, where we define “innovation” within knowledge-based organizations as the purposive use of knowledge to provide a new solution to a problem that creates value.

In research libraries and special libraries, we argue new leadership, oriented around innovation, is needed to encourage mission-driven research and actions. We frame this within three types of institutional innovation, ordered by their potential for effect – and also difficulty in implementation – with the third mode (“Type III”) designated as having the most potential for impact. Table 1 illustrates the distinguishing characteristics between the three types, along with their ease of implementation for leadership.

Table 1

Three types of institutional innovation

| Type I | Type II | Type III | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Interventions | Attitudes | Systems-based |

| Vectors | Beliefs | Core-transformative | |

| Quick hacks | Trendy ideas | Revolutions | |

| Ease of implementation | Easy to sell | Easy to sell | Hard to sell |

| Easy to implement | Hard to implement | Really hard to implement | |

| Easy to measure | Hard to measure | Really hard to measure |

Type I innovations consist of interventions, vectors, and quick hacks. They are “easy to sell.” That is, their key ideas are simple to communicate and support for the ideas is easy to build. Implementation is also generally easy as only a simple intervention is needed, which is likewise easy to measure. Institutional impact is predicted to become low as simple interventions rarely create core transformations.

Type II innovations are centered around attitudes, beliefs, and trendy ideas. Like Type I innovations, they are easy to sell, but implementation and measurement are difficult. One example is building creativity into an organization. We imagine few leaders would believe building greater creativity into an organization is a bad idea, but developing a more creative organization is a challenge to implement. It can also be challenging to maintain momentum of a creative endeavor. And, within creative organizations, the extent to which one is creative is challenging to measure.

Type III innovations are built upon true revolutions that interact on a systems level with the knowledge organization to transform the core or “heart” of the institution. This is often expressed as creative destruction: tearing down the structure and culture of an organization and rebuilding it into something new. These innovations are hard to sell, as very few people want a total revolution in their organization. And, like a revolution, they are very hard to implement. Further, they touch so many core areas of the organization that measurement becomes very difficult (unless macro-level, post-hoc methods of measurement are used, such as asking, “did the institution survive the revolution?”).

Within this framework, we recognize that while some innovations may be preferred over others, each of the three types can create value for a knowledge-based organization. More importantly, innovations from the three types may interplay and integrate with each other, contributing to the goals or desired outcomes of others. A Type I or Type II innovation may very well fall within the overall strategic framework of a Type III innovation.

Table 2

Examples of the three types of institutional innovation in research libraries and special libraries contexts

| Type I | Type II | Type III |

| Virtual delivery of services and content | Transforming library into collaborative spaces | Library laboratories |

| Mobile applications | Blended librarian | Invisible and tacit learning |

| Institutional repository development | Expanded library | Knowmadic places |

Type I institutional innovation examples include the virtual delivery of services and content, the use of mobile applications, and the development of institutional repositories. In the past, the main purpose of academic libraries was to provide materials needed immediately by users and to store materials for future use. However, as the current landscape continues to shift toward greater digitization of information, libraries have begun doing the same. Rather than serving as a storehouse for print items such as books and journals, libraries are digitizing and storing content in institutional repositories for more immediate access and use. Further, libraries are investing in services and tools to enhance the discovery, access, and use of information (Levine-Clark, 2014). Consumers are able to access library resources at any hour, any day, and helpdesks are now available online. As end users move toward utilizing their own mobile devices, libraries are working to deliver content to them. Content and services are delivered via email, text messaging, instant messaging, and social networking services (Dysart, Jones, & Zeeman, 2011). Content is increasingly streamed to classrooms (Jantz, 2012). In addition to traditional printed materials, eBooks are becoming more popular and accessible. In fact, libraries are buying fewer print materials as they make the shift to digitization of resources (Dysart et al., 2011; Levine-Clark, 2014). These Type I innovations are easy to communicate and garner support from end users within the organization. Implementation, effectiveness, and degree of success are simple to measure. The overall impacts of these innovations, however, remains relatively low, as the core functions of a library remain static.

Type II institutional innovation examples include transforming libraries into collaborative spaces, blended librarians, and expanded libraries. As libraries continue downsizing their print collections in favor of digitized access of information, physical space is increasingly available for use in different and more flexible ways (Dysart et al., 2011; Jantz, 2012; Sinclair, 2009). The reinvention of these spaces for social, technological, and cultural uses provides new opportunities for co-working, collaborating, and delivery of specialized trainings (Sinclair, 2009). Some libraries house coffee shops and dining establishments. These changes in the ways library spaces are used and the continued digitization of resources has shifted the responsibilities of the librarian toward becoming “blended librarians.” They are less focused on transactional services and provide more people-intensive services toward improving end users’ experience (Dysart et al., 2011). Their focus is blending library skills, information services, ICT, and instructional design. Blended librarians collaborate with information technology departments to develop skills with online tools, software, multimedia, and mobile applications (Bell & Shank, 2004; Sinclair, 2009). They further expand beyond the walls of the physical library (Sinclair, 2009), collaborating with many different departments, embedding themselves within project and work teams, using their skills to develop services specific to the needs of the staff with whom they work (Dysart et al., 2011). These shifts from the traditional “pull” approach of library use toward a “push” style of engaging the community and working with consumers have extended the reach of the services and content available through the library. These Type II innovations are centered on the beliefs that work is collaborative in nature and the library’s role is to accommodate consumers through availability and accessibility, physical space, and support. These ideas are relatively easy to market internally, however, implementation and the measurement of success of these ideas are more difficult.

Type III institutional innovation examples include library laboratories, invisible and tacit learning, and knowmadic places. Some libraries are beginning to transform into laboratories and maker spaces to encourage user collaboration using traditional library materials combined with other types of creative and innovative resources (Colgrove, 2013). They provide tools, machines, and workshops designed for experimentation and development (Berry, 2012). Tools such as projectors, 3D printers, and large screen monitors are available for use (Berry, 2012; Colgrove, 2013; Sinclair, 2009). Users also have access to studios for producing their own photography, audio remixing, videos, and digital media such as podcasts and blogs (Berry, 2012; Colgrove, 2013). The focus of simply usinglibrary resources and materials is shifting toward actually creating with them (Colgrove, 2013). Invisible learning spaces enable library users to develop knowledge through non-formal and informal approaches, often employing “do-it-yourself” or hacker-like thinking to develop new understandings and solutions to challenges and opportunities (Cobo & Moravec, 2011). Knowmadic places create, through design, emotional links between spaces and their users, supporting the abilities of individuals to think differently, while flattening hierarchies (Noriega et al., 2013, p. 144). These Type III innovations transform what was once considered the purpose of a library: from one that houses and makes available resources and materials to consume, toward something that is very different from a traditional library “blueprint” and the formation of something unique to the host organization. These revolutionary ideas, because they are so transformative and question the very “fabric” of traditional organizations, are hard to sell, implement, and measure.

It is important to note that while the potential to create impact is obviously greater in Type III innovations, we should not downplay the importance of the other two types – each of these types of innovation have value. Strategic leadership for organizations that support knowmadic entrepreneurship (and intrapreneurship) requires approaches that address interdisciplinary, systems integration of knowledge-based work. These require a transformation in the way libraries operate, from looking at interventions and vectors toward creating real organizational change: systems-based, core-transformative, and those that challenge our key assumptions about how we relate, learn, and collaborate with each other. This means considerations should be made as to how to feed Type I and Type II initiatives into a greater Type III revolution.

For these revolutions to have impact, libraries need to reframe why, how, and for whom they exist and explore new pathways to realize these functions. From an organizational standpoint, this suggests libraries (and their leaders) need to build a metacognitive sense of the institution: an awareness of what is not known about the organization, its goals, and methods. Only then is it justifiable to engineer breaks from the system that challenge the status quo and enable Type III transformations to flourish.

An example pathway for maximizing organizational creativity and innovation capital

Type III innovations, at their core, engage with (and challenge) organizations to employ more creative resources toward solving a greater, mission-driven problem. As the challenges are greater, they resemble a “Noble Quest” for transformative leadership.

As an example of one such Type III goal, to support knowmadic workers and learners, the library can be transformed into a knowmadic hub, where new knowledge creation and the contextual application (doing) of knowledge are facilitated, in contrast to the traditional role of a library as an information repository. This transforms the space into one of knowledge brokerage (see Meyer, 2010) and action. The library, as a knowmadic space, could incorporate other innovations, such as the virtual delivery of services (Type I) and the transformation from stacks of resources to collaborative spaces (Type II).

The library as a knowmadic hub is centered on sharing knowledge, expertise, and ideas, connecting an organization’s people and other actors together to create purposive value. As organizations become less hierarchical in function and increasingly operate as mesh networks (see esp. Allee, 2003; van den Hoff, 2011), the knowmadic library and its librarians can find new roles in serving as connecting hubs, particularly with smart, purposive applications of ICTs.

In lieu of conclusion, spaghetti needs meatballs

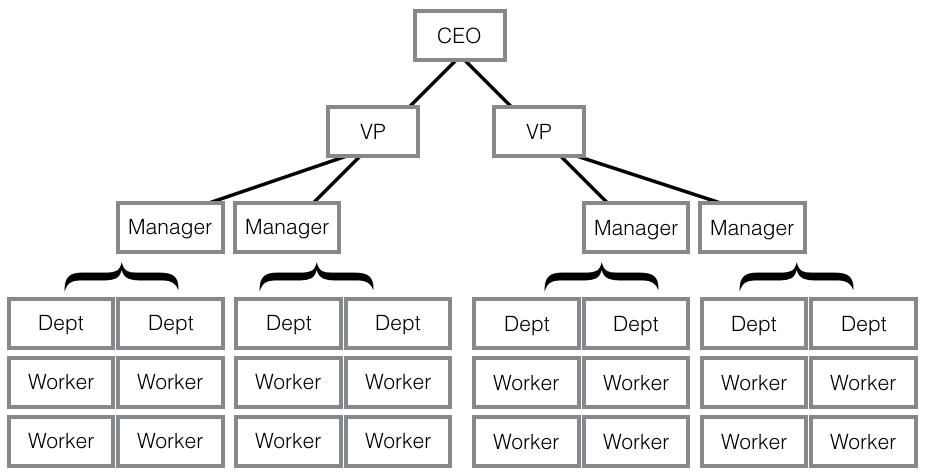

Figure 1. A traditional, formal organizational chart.

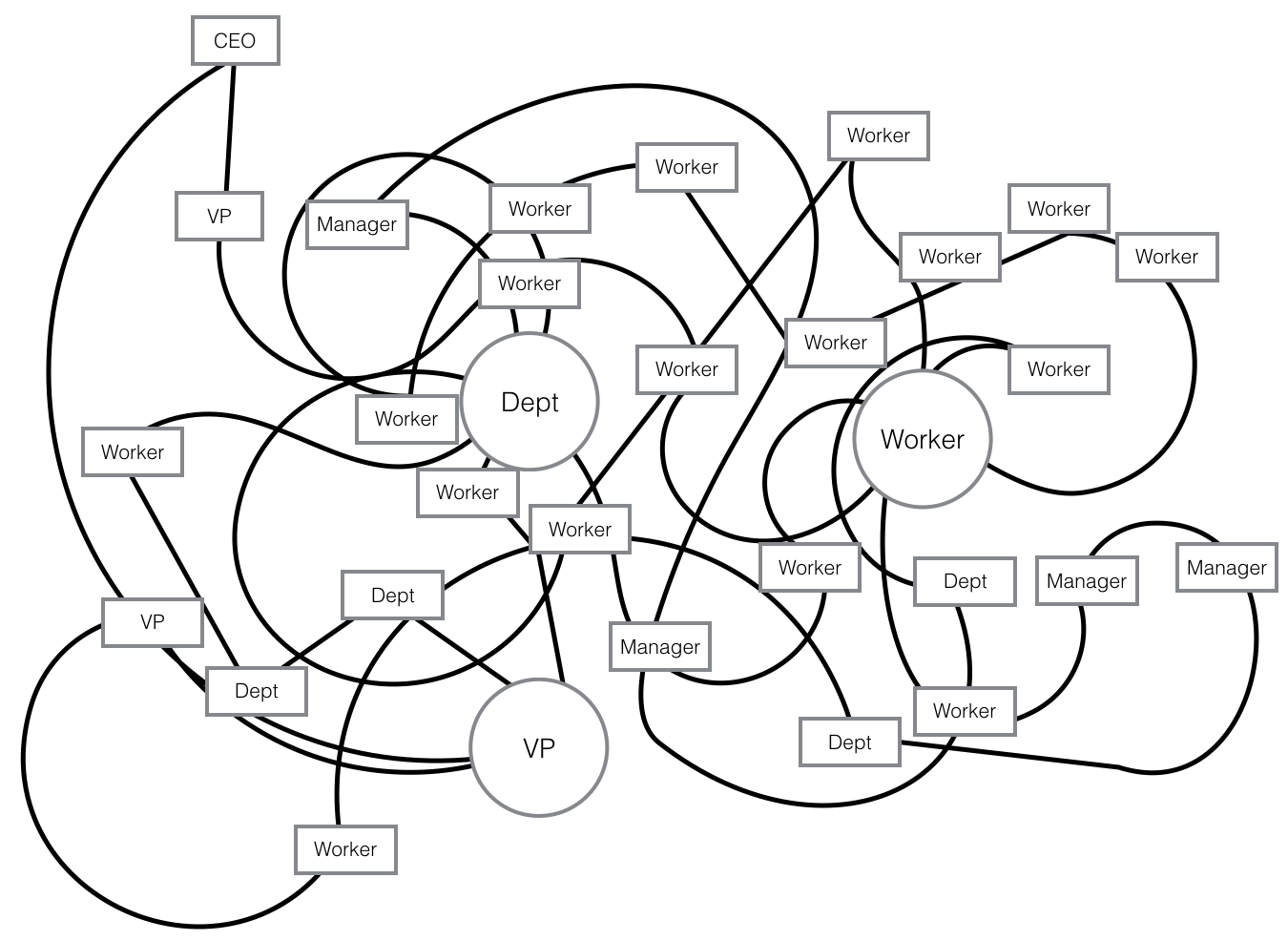

Figure 2. A value-oriented knowledge organization.

Organizations that are driven by value networks and knowmadic knowledge can seem messy. While they may still maintain top-down organization charts, the operation may appear chaotic to an observer. Allee (2003) writes:

Much of the chaos that results from organizational change efforts arises not from trying to do something new, but from careless disregard of the complex system or systems that will be changed or affected in the process. Organizations evolve along multiple dimensions. When organizations change, old patterns of relationships are dismantled and reassembled into new configurations. People can better see where to make needed adjustments in their own activities without wreaking havoc on the whole system if they more fully understand the essential exchanges and relationships that create value. (p. 194)

When Allee maps how these organizations function as value networks, they no longer appear as orderly, top-down operations with clear lines of relationships (Figure 1). Rather, they appear as complex strings of spaghetti with multifaceted connections flowing between and among various levels and spans of an organization (Figure 2). In such a configuration, certain individuals and departments emerge as larger players (“meatballs”), with greater connections across various levels of the institution; some meatballs are larger than others.

As knowmadic hubs, libraries become super-connectors, knowledge brokers, and facilitators of invisible learning within the institution. Perhaps appearing as a large meatball in a map of the organization’s spaghetti-like, mesh network, added value is created for its users and stakeholders by brokering new opportunities for knowledge development and innovative actions.

In this rapidly-changing world, where information is literally at the tips of our fingers and an institution’s ability to act on knowledge drives its potential for success, does the future need libraries? Or, does it need meatballs?

References

- Allee, V. (2003). The future of knowledge: Increasing prosperity through value networks. Amsterdam ; Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Baumol, W. J., & Towse, R. (1997). Baumol’s cost disease: The arts and other victims. Cheltenham, UK ; Northampton, MA, USA: E. Elgar.

- Bell, S. J., & Shank, J. (2004). The blended librarian a blueprint for redefining the teaching and learning role of academic librarians. College & Research Libraries News, 65(7), 372-375.

- Berry, A. (2012). How libraries are reinventing themselves for the future. Retrieved from http://newsfeed.time.com/2012/06/22/how-libraries-are-reinventing-themselves-for-the-future/slide/how-libraries-are-reinventing-themselves-for-the-future/

- Christensen, C. M. (1997). The innovator’s dilemma: When new technologies cause great firms to fail. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Cobo, C., & Moravec, J. W. (2011). Aprendizaje invisible: Hacia una nueva ecología de la educación. Col·lecció Transmedia XXI. Barcelona: Laboratori de Mitjans Interactius / Publicacions i Edicions de la Universitat de Barcelona.

- Colgrove, P. T. (2013, March). Editorial board thoughts: Libraries as makerspace? Information Technology and Libraries, 32(1), 2-5. Retrieved from http://ejournals.bc.edu/ojs/index.php/ital/article/viewFile/3793/pdf

- Dysart, J., Jones, R., & Zeeman, D. (2011). Assessing innovation in corporate and government libraries. Computers in Libraries, 31(5), 6+.

- Gibbons, M., Lomoges, C., Nowotny, H., Schwartzman, S., Scott, P., & Trow, M. (1994). The new production of knowledge: The dynamics of science and research in contemporary societies. London: Sage.

- van den Hoff, R. (2011). Society 3.0. Utrecht: Stichting Society 3.0.

- Jantz, R. C. (2012). Innovation in academic libraries: An analysis of university librarians’ perspectives. Library & Information Science Research, 34(1), 3-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2011.07.008

- Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago.

- Kurzweil, R. (2005). The Singularity is near: When humans transcend biology. New York: Viking.

- Levine-Clark, M. (2014). Access to everything: Building the future academic library collection. Libraries and the Academy, 14(3), 425-437. doi: 10.1353/pla.2014.0015

- Meyer, M. (2010). The rise of the knowledge broker. Science Communication, 32(1), 118–127. http://doi.org/10.1177/1075547009359797

- Moravec, J. W. (2008). Knowmads in Society 3.0. Education Futures. Retrieved from /2008/11/20/knowmads-in-society-30/

- Moravec, J. W. (2013a). Introduction to Knowmad Society. In J. W. Moravec (Ed.), Knowmad Society. Minneapolis: Education Futures.

- Moravec, J. W. (2013b). Knowmad Society: The “new” work and education. On the Horizon, 21(2), 79–83. http://doi.org/10.1108/10748121311322978

- Noriega, F. M., Heppell, S., Bonet, N. S., & Heppell, J. (2013). Building better learning and learning better building, with learners rather than for learners. On the Horizon, 21(2), 138–148. http://doi.org/10.1108/10748121311323030

- Polyani, M. (1966). Chapter 2: Emergence. In The Tacit Dimension (pp. 29–52). New York: Doubleday.

- Sinclair, B. (2009). The blended librarian in the learning commons: New skills for the blended library. College & Research Libraries News, 70(9), 504-508.

- Zenke, P. F. (2012). The future of academic libraries: An interview with Steven J Bell. Retrieved from /2012/03/26/the-future-of-academic-libraries-an-interview-with-steven-j-bell/

Special thanks to Patricia Avila (INFOTECH), Wouter Schallier (United Nations-CEPAL), and Giovanna Valenti (FLACSO México) for their remarks as panel discussants at Congreso Amigos 2015. Additional thanks go to Alejandro Pisantyand Cees Hoogendijk for the commends on the draft document on academia.edu.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.