John Moravec

John MoravecSecond channel resilience: Preserving educational coördination in low-connectivity environments

Field notes

I thought it would be interesting to share some research notes from an exploratory inquiry into whether LoRa-based mesh communication can support learning and teacher professional development programs when electricity and internet access remain unreliable. I do not present this as a definitive evaluation of LoRa or Meshtastic, but as field-informed experimentation intended to clarify where low-data mesh networking fits, what it enables, and what limits it. This work was performed throughout 2025.

The project reported here constitutes exploratory research into low-data communication for education in low-connectivity environments. It emerged from my experience in Sierra Leone connected to a digital coaching initiative, where coaching and learning activities continued locally while the return flow of program data repeatedly failed under unstable electricity and intermittent internet access. In practice, devices existed and effort existed, but the coördination layer degraded. Observations, checklists, and follow-up notes remained stranded on phones or paper. Program leaders then faced a familiar problem: decisions had to be made with partial visibility.

This constraint reframed the technical question. Rather than asking how to deliver richer online learning experiences, I asked what minimal information must move for an education program to remain responsive. Many educational systems can tolerate delays in content delivery, but they cannot tolerate persistent breakdowns in coördination. Scheduling, basic reporting, safety and access updates, and short guidance for teachers and facilitators often matter more than real-time media. I therefore focused on whether a resilient, low-bandwidth second channel could carry essential messages when the primary channel fails. By “second channel,” I mean a parallel path for small packets of coördination data that continues to function when conventional internet connectivity drops out.

The technical candidate was LoRa, a long-range, low-power radio technology that has been used for years in telemetry and sensor networks. What has shifted more recently is not the existence of LoRa, but the accessibility of user-configurable mesh tools that allow communities to build store-and-forward communication across real landscapes using inexpensive nodes. A common entry point is a small Meshtastic-compatible LoRa board such as a Heltec WiFi LoRa 32 (V4) or a LilyGo T-Beam. As of early 2026, typical retail pricing for these basic nodes sits in the approximate USD $20 to USD $40 range, before accessories such as higher-gain antennas, enclosures, or batteries.

Implementations such as Meshtastic make it plausible to deploy ad hoc mesh networking without specialist infrastructure, thereby extending LoRa from point-to-point use toward geographically distributed community communication. My interest in this shift was practical: if messages can travel through a mesh that tolerates delay and intermittent paths, then education programs might preserve core coördination functions even when internet service is absent. Because the network can be owned and maintained locally, it can also increase operational autonomy by reducing dependence on external operators, contracts, or centralized permissions.

| Feature | Conventional Broadband (Primary) | LoRa Mesh (Resilient Second Channel) |

| Primary goal | High-throughput content delivery | Low-data coördination and persistence |

| Connectivity | Continuous / Real-time | Intermittent / Asynchronous |

| Data payload | Large (Video, Rich Media, Syncing) | Tiny (Text, Codes, Numeric Scores) |

| Infrastructure | Centralized towers/ISP | Decentralized, community-owned nodes |

| Power needs | High (Requires stable grid/fuel) | Very Low (Solar/Battery-powered) |

| Failure mode | System blackout on signal loss | “Store-and-forward” (Delays but delivers) |

The power budget is as important as the radio link. Meshtastic’s own guidance frames typical node power draw in the range of a few hundred milliwatts under common configurations, which is low enough that a small power bank can keep a node running for days, depending on duty cycle, screen use, and whether GPS is enabled. In the same logic, small solar setups become plausible: devices designed for long-term deployment commonly pair a modest battery pack with a 5W panel to sustain operation in off-grid conditions, provided the installation has adequate sunlight and the configuration is tuned for efficiency.

This work is approached with an assumption that similar infrastructural constraints operate across multiple high-need contexts. Refugee settlements often combine high coördination demand with constrained power budgets and restricted network availability. In settings where access is socially or politically constrained, including initiatives supporting girls’ education in Afghanistan, conventional network-dependent models can become fragile or infeasible. These are distinct environments, but they share a common design pressure: systems must function when connectivity appears intermittently and unpredictably. Under these conditions, communication architectures that prioritize eventual delivery and low energy consumption may offer operational value, even if they cannot support high-throughput applications.

I emphasized practical behavior under imperfect conditions rather than laboratory benchmarking. This included an examinatino of hardware feasibility, message delivery patterns, and the plausibility of educational workflows that can tolerate latency, partial loss, and limited payload size. I used Meshtastic as a testbed because it provides text-based messaging, store-and-forward routing, and automatic mesh formation among battery-powered nodes. My intent was to understand what educational tasks the medium can support and what kinds of environments undermine it.

In practice, the user interface does not require typing on the radio itself. Most deployments pair the node to an existing smartphone over Bluetooth, and the user composes messages in the Meshtastic mobile app, which keeps the interaction pattern familiar even when the transport layer is not.

I structured the exploration around three use cases. Each reflects a different educational function: program monitoring, community coördination, and instructional support. Together they allowed me to evaluate whether LoRa mesh networking supports only interpersonal messaging, or whether it can sustain elements of the information infrastructure that education systems often assume will be delivered through broadband.

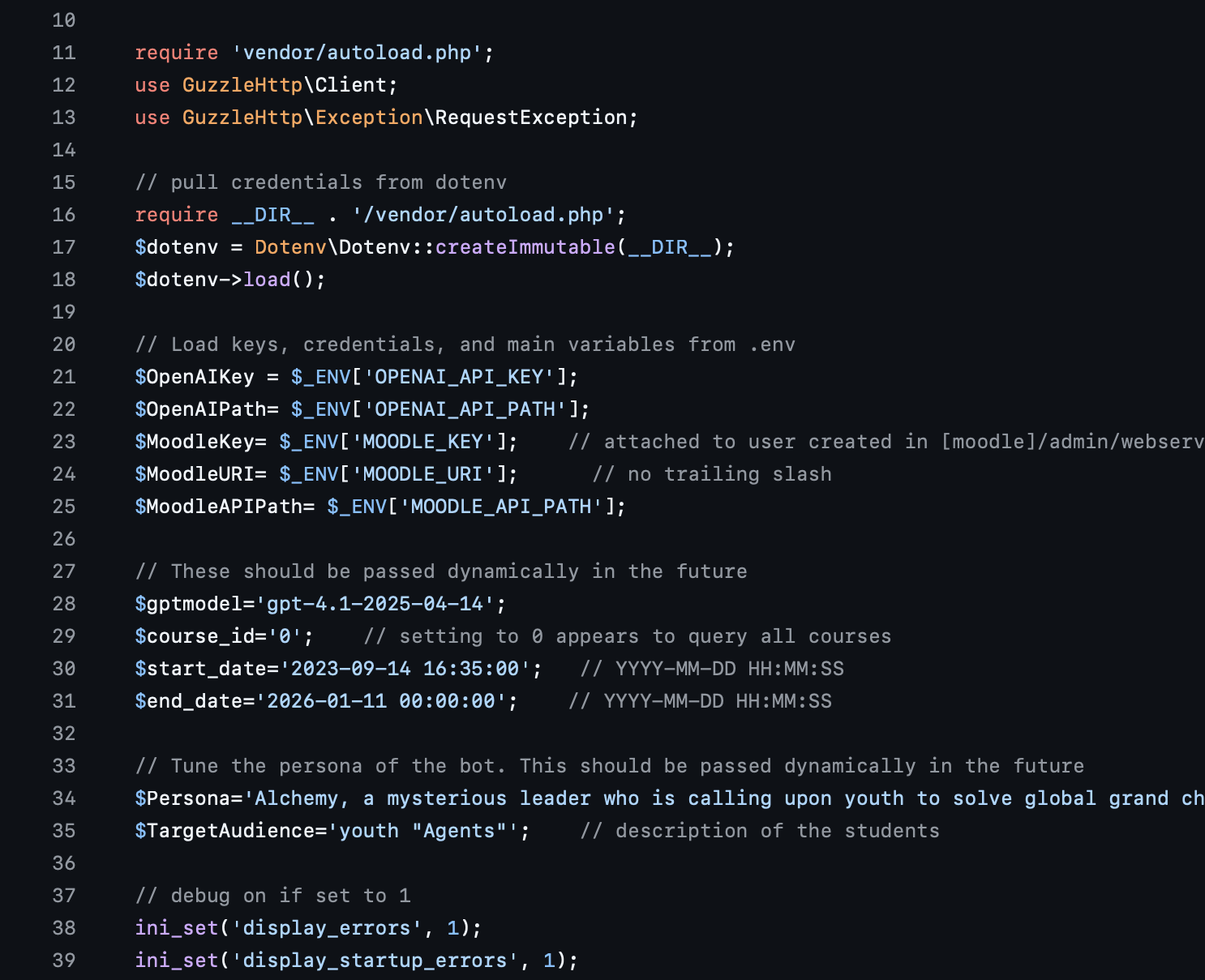

The first use case addressed a central operational need in educational improvement programs: returning structured data for centralized collection and analysis. Observation-based frameworks and coaching models depend on the ability to aggregate results, identify trends, and respond through targeted support. In many low-connectivity settings, the bottleneck is not collecting data at the point of practice; it is transmitting it in a timely and reliable manner. I explored whether observation checklists, numeric scores, and short annotations could be encoded into compact message payloads and transported through a mesh to a location where data can be consolidated. In a simple workflow, a coach submits a coded message locally, intermediary nodes forward it opportunistically, and a gateway node later synchronizes with a laptop or other upstream channel when connectivity becomes available.

One practical way to implement that upstream handoff is to place a single gateway node near intermittent internet access, for example a school office that sometimes has Wi-Fi, or a location where a shared 3G hotspot appears periodically. When configured for MQTT, that node can uplink the mesh packets it observes to an MQTT broker whenever it sees connectivity, effectively pushing queued field messages to cloud services without requiring every participant to have internet access. In effect, the gateway acts as a bridge that “drains” queued messages from the mesh into a cloud database whenever an uplink becomes available.

This use case appeared most promising when aligned with the realities of program timelines. Many monitoring systems do not require minute-by-minute reporting; they require regular and trustworthy reporting. When messages arrive within hours or within a day, they can still support program oversight, quality assurance, and feedback planning. Under that lens, the key requirement becomes reliability under delay rather than immediacy. That requirement matches store-and-forward mesh logic more closely than it matches conventional web platforms optimized for constant synchronization.

The second use case examined a community information layer that resembles bulletin board systems in its basic logic. Such systems assume asynchronous participation, local relevance, and limited bandwidth, all of which map well to LoRa constraints. Within a mesh, a lightweight posting and retrieval model can support announcements, schedules, short guidance notes, and peer-to-peer exchange without requiring a centralized server. Educational value emerges through routine coördination that often gets overlooked in technology planning: notifying facilitators about meeting times, communicating changes in access or safety, sharing local lesson adaptations, and routing questions to peers. When the system operates through persistence and eventual delivery, it can sustain coördination despite intermittent connectivity, provided that participants accept that communication does not always occur in real time.

This community layer also highlighted a behavioral effect of constrained bandwidth. When participants must write within strict limits, they often produce shorter, more deliberate messages. That constraint can reduce low-value chatter and privilege information that others can re-use. The effect depends on context and norms, but it suggests that low-bandwidth systems may support a distinct communication culture that differs from real-time chat platforms, with potential benefits for community coördination.

The third use case explored whether AI-mediated instructional support can be adapted to a low-data environment. I treat this as speculative because contemporary AI delivery models typically assume continuous interaction, stable connectivity, and large context windows. A constrained alternative is nonetheless conceivable. Devices can be preloaded with curated instructional resources, and the mesh can distribute prompts, mini-lessons, or short guidance packets authored centrally. Users can submit short queries or requests, and responses can be returned asynchronously when routes permit. Under this model, AI functions less as a conversational tutor and more as delayed coaching support, structured reference assistance, or guided practice that arrives in discrete chunks.

The primary limitation here is pedagogical rather than technical. Short queries often strip away situational context that makes guidance relevant. Delayed responses weaken dialogue and reduce opportunities for clarification. As a result, the strongest applications likely involve structured tasks, procedural guidance, and frequently asked questions rather than open-ended tutoring. Even within those constraints, this approach may hold practical value where qualified teachers are not consistently available, especially if positioned as support for local facilitation rather than as a replacement for human instruction.

| Task Category | Example Activity | LoRa Suitability | Constraint to Manage |

| Monitoring | Classroom observation scores | High | Requires coded templates (e.g., “Q1:4”) |

| Coördination | Change in meeting time/location | High | Latency (may take 1–30 mins to propagate) |

| Instruction | Weekly teaching tip (short text) | Medium | Must be under ~200 characters |

| Support | AI-mediated Q&A | Low | Requires heavy distillation/summarization |

| Materials | Sending a 10-page PDF manual | Impossible | Requires physical distribution (e.g., SD card) |

Across all three use cases, system behavior depended strongly on the interaction between radio propagation and landscape. The technology can perform reliably in settings where nodes maintain line-of-sight or where obstructions remain limited. Performance degrades in environments where dense vegetation, uneven terrain, and certain building materials attenuate or scatter radio signals. Dense tree cover can reduce effective range. Elevation changes can create signal shadows that fragment routes. Built environments can add complex losses depending on materials and layout. These conditions are not incidental; they are often the default in rural and peri-urban settings where education programs operate under constraint.

These environmental sensitivities shape a key practical implication: LoRa mesh networking shifts some reliability requirements away from software and toward deployment topology and maintenance routines. Increasing transmission power can help at the margins, but it cannot substitute for well-placed relay nodes when the landscape imposes structural barriers. Mesh density and strategic placement therefore matter at least as much as device specifications. In practice, the system becomes partly social infrastructure. Someone must host nodes, charge devices, notice failures, and maintain placement. Reliability becomes a function of both physics and stewardship.

These constraints also clarify the scale at which LoRa mesh networking fits educational needs. The approach appears best suited to bounded geographies where participants share space and purpose and where relay placement is feasible. Refugee camps match this profile because they combine density, coördination need, and constrained connectivity, and because a small number of strategically placed nodes can potentially provide robust coverage. Rural school clusters can also fit when schools are close enough to sustain a mesh and when communities can support relay placement at higher elevations or along travel corridors. Informal settlements may fit when local organizations can maintain devices and establish norms for use. At larger regional scales, the requirement for node density and the cumulative effects of environmental attenuation make the approach less practical without additional infrastructure layers. In some settings, the ability to coördinate locally without routing every interaction through centralized platforms is part of the value proposition, especially when trust and safety are live constraints.

A further implication concerns the relationship between low-data transport and the educational software stack. LoRa mesh networking can move messages, but it does not by itself create structured data collection, user workflows, or meaningful feedback loops. For monitoring and coaching, programs still require offline-first tools that support local storage, clear data entry formats, and synchronization strategies that treat delay as normal. For community coördination, systems still require message conventions, moderation norms, and routines for ensuring that critical notices propagate. For instructional support, systems still require curated content, task design, and safeguards against over-reliance on decontextualized guidance. In this sense, LoRa functions as a transport layer that can complement offline-first educational systems, but it cannot substitute for them.

I take from this work a broader design stance for education technology in constrained contexts. Systems should treat interruption and delay as baseline conditions rather than as exceptional failures. Many platforms designed for stable connectivity respond poorly to partial synchronization, producing inconsistent records and eroding trust. LoRa mesh communication encourages a more resilient approach: identify the minimal information flows that keep programs accountable and responsive, then engineer those flows to tolerate scarcity, delay, and intermittent paths. This stance does not resolve the structural inequities that constrain educational opportunity, and it should not be framed as an alternative to universal, affordable internet access. It does, however, provide a pragmatic option for preserving coördination and feedback when conventional network dependencies repeatedly fail.

A practical next step would be a pilot designed explicitly for a bounded community setting, with refugee camp education coördination representing a strong candidate based on the fit constraints observed. Such a pilot would specify the minimal data types to be transported, establish message templates and coding conventions, deploy a modest number of relay nodes based on terrain and obstructions, and implement simple maintenance routines for charging and monitoring node health. Evaluation would focus on delivery reliability under real operating conditions, the ease of community stewardship, and the effect on program responsiveness, particularly the speed and completeness with which observation and coördination information reaches decision-makers.